Pushing past the blocks

The school gymnastics team shares how they work through the mental challenges in their sport

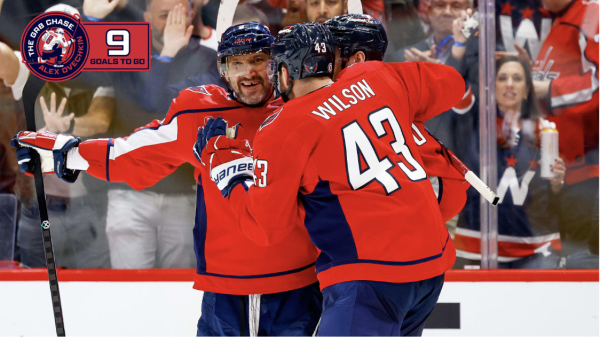

A student on our gymnastics team mid-flip. Some gymnasts suffer from mental blocks which stop them from completing some moves.

Junior Alexa Brooke, a member of the school gymnastics team, takes off, running across the floor of the gym, preparing to launch into a roundoff backhandspring back tuck. Brooke had injured herself while completing this skill not long ago, but after healing she knows she is physically ready to try again. Despite her determination, however, Brooke stops before completing the technique. She simply cannot make herself go for it. Situations like these are called “mental blocks” and they are actually quite common within the sport of gymnastics.

“[Coming back from the mental block] was definitely very difficult mentally and it made me pretty stressed,” Brooke said. “I wouldn’t really want to go to floor during practices because I knew that I would have to do [that skill] and it just made me anxious.”

“I would always say to my coaches ‘I want to go. I want to do the skill,’” senior Devin Nemirow, who has been a member of the school gymnastics team since freshman year, said about her own mental block on the beam. “But you’d stand up there, you get ready, and it’s like your body’s blocking you. I can swing my arms for a backhandspring as many times as I want, but I’m never going to jump.”

While gymnasts have been dealing with mental blocks for as long as they have been doing the sport, it was brought to the attention of most of the world this summer when USA Gymnastics gymnast Simone Biles, who is colloquially known as the greatest gymnast of all time, stepped back from the team competition in the Olympics after experiencing “the twisties.”

“Mental blocks and twisties are a little bit the same, a little bit different,” Nemirow said. “Twisties is more perceptual, being dizzy in the air and at that point a fear for how you’re going to land … mental blocks kind of go hand in hand where when you have those scary feelings like [Biles] did, she probably developed a bit of a mental block. Now [that] she’s had that scary experience, she can’t just go up and try it again, it’s not that easy.”

While Nemirow has never experienced the twisties herself, she, like most other gymnasts, has had her share of mental blocks. For many of these athletes, seeing Biles take a step back was inspiring, despite being met with backlash from other viewers who saw Biles’ decision as “selfish” or “weak.”

“I think that by stepping out of the Olympics, [Biles] chose the safest option for her,” senior, three-time MVP and captain of the school gymnastics team, Grace Chen, said. “Continuing on from her disorientation could have resulted poorly. Her stepping back and speaking about her problems brought awareness to the mental aspects of gymnastics.”

Mental blocks and the twisties are common within the sport. When paired with grueling hours, constant striving for perfection and tough coaches, the sport is both physically and mentally tough.

“Mental health is 100% not talked about enough in the gymnastics community,” senior, and member of the school gymnastics team, Sophia Bailey said. “Most high level gymnasts start when they are extremely little, and because of this they believe the way it is is the way it’s supposed to be … Hearing only criticism for years (about my gymnastics, my body, my personality) was extremely dejecting, especially at such an impressionable age. Adults and parents need to be more in tune with what is going on with gymnasts’ minds.”

Coming back from a mental block or the twisties can be a long and frustrating experience. Chen is currently fighting a mental block on the bars, and has been for about nine months. Typically, the process involves building back up from easier skills, sometimes relearning those as well.

“I have complete faith in [Biles] for rebuilding that mental stability and getting the twisties out of her head,” Nemirow said. “It will definitely take time but, then again, we have three years until the next Olympics, so she has a while. But there are plenty of competitions in between for her to regain her confidence.”

A supportive environment can be very beneficial in overcoming these blocks and generally dealing with what can be a mentally draining sport. While the school team is said to be positive in this regard, other club teams do not have the same reputation.

“Gymnastics and I have a very complicated and rocky relationship,” Bailey said. “When I was younger, I absolutely loved it … But as I got older, I noticed more things about the sport that I hadn’t before. My coaches were over-critical and mean … They would make comments not only about my skill, but about my body or my hair, both things I couldn’t control. There was a period of time where I cried on the way to the gymnastics gym every time I had practice. It took me a long time to enjoy gymnastics again and to ditch the negativity and anxiety that I attributed with the sport.”

Adding to the stress of the sport is the amount of time that must be put in. Gymnastics is a year-round sport for those that participate in club teams. For Chen, who is a level nine Junior Olympic gymnast on the Arlington Aerials, this means 20 hours of training a week. There are, however, other options. Brooke is a member of the Arlington Aerials Xcel platinum team, which practices nine hours a week in order to allow for a more flexible schedule. Despite many benefits of the sport, the strenuous practice hours cut into social and family life.

“Your life kind of revolves around gymnastics. I did not really have friends until high school, when I was able to do the sport with people in my school,” Nemirow said. “They definitely keep track of attendance, which is stressful, because if you have to miss [gymnastics] for a family emergency now you’re worried about ‘Oh, I had to miss gymnastics, that’s points off my attendance,’ rather than, ‘Oh, I had a family emergency, I should really deal with this right now.’”

In comparison, the school team requires less of a commitment, only practicing about five hours per week. The coaches, Joe D’Emidio and Ronald Melkis, have a good reputation when dealing with mental health, according to Nemirow, and taking a step back is acceptable with 20 athletes on the team and only six competing in each event per week.

“The W-L gymnastics team is super supportive and we all get along really well,” Chen said. “The past few years we have won districts and regionals. That is definitely the highlight of the season.”

Chen added that throughout the last competition season, one of her teammates would stand under the bars during her routine for extra support as she works through a mental block. This year, the team hopes to once again win districts and regionals, as well as do well at states.

“Even though we do make it to states every year we are a kind of carefree team who lets anyone, pretty much, compete,” Nemirow said. “We’re happy for a small success, even if it’s a basic skill for a newbie rather than a huge skill for a returner, it’s just the same. It’s so cool to see everyone try gymnastics because it’s what we’ve all been doing since we were two.”

“Because most of us have done competitive club gymnastics in the past, we know that being a positive and uplifting team is massively important,” Bailey said. “We all support one another whether it is in relation to gymnastics, school, or personal lives.”

In a sport like gymnastics, which emphasizes perfection, taking a step back, like Biles did, was largely unheard of. Biles’ choice reflects that conversation around mental health in the sport has begun to increase in recent years. Nemirow cited a mindset trainer who visited her team about two years ago. The trainer worked with them to understand the psychology of gymnastics, which, according to Nemirow, would have been unheard of in her younger years as a gymnast. Still, the hope for many is that Biles’ decision this year will further bring to light the stress put upon gymnasts and the importance of dealing with these issues.

“[In gymnastics] you’re not working to score a touchdown, you’re working to be perfect because you’re being scored on everything you do,” Nemirow said. “When you’re getting scored on every competition you realize judgement more so then when you’re in school [it’s] ‘Oh, I have to get A’s, I have to do perfect at competitions, I have to be a perfect sibling, I have to be perfect at everything.’ I think taking a step back and saying ‘I can be good at some things and I can be great at some things and I can be not so good at some things and that’s okay because I’m not being judged. I’m myself and I don’t need to be perfect’ [is important]. You don’t have to do your homework perfect. It’s going to be okay.”