Senior Thomas Ackleson acts to attack cancer early

Student spent his summer working on AI to diagnose cancerous lesions

Over the summer, W-L senior Thomas Ackleson spent his time in a rather unusual way for a high schooler. While others were going on vacation and working summer jobs, Ackleson was working on impressive Artificial Intelligence (AI) technology with Stanford masters students that has the potential to help millions of Americans in the future.

According to the American Academy of Dermatology, one in five Americans will get skin cancer in their lifetime. This is a staggering statistic, and it becomes even bleaker for the nearly 10 percent of Americans who can not afford health insurance. For these 33 million people, going to the doctor’s to get a spot or lesion checked out may not always be in the cards financially. This leads to cancer being found too late, past stages where it could have been curable. What Ackleson and his team worked on over the summer will potentially allow those without health insurance to determine what their condition is and whether or not it will need treatment.

One of the most exciting aspects of the AI that Ackleson helped develop is the accuracy level.

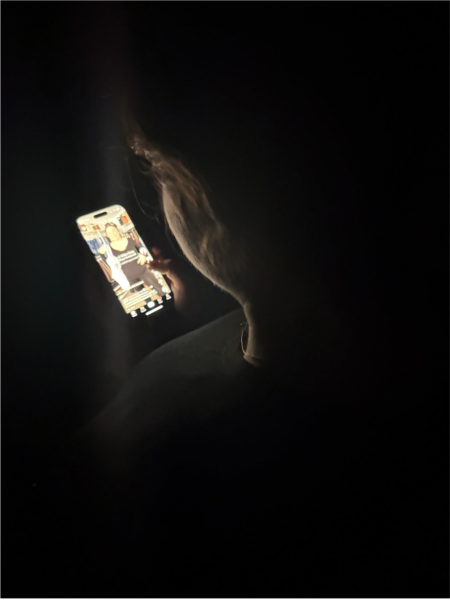

“The accuracy of the model is significantly higher for identifying cancerous or non cancerous lesions than most US dermatologists by [roughly] 10 to 15 percent,” Ackleson said. “The technology would [provide many benefits] if implemented into an app, [where] users could use the camera on [their] smartphone to scan [concerning areas on their body] and [possibly] diagnose, to a high degree of certainty, what sort of lesion [they] have.”

With this AI, Ackleson believes the sky is the limit.

“There is definitely room for improvement,” Ackleson said. “Our research was [mainly focused on] differentiating between seven unique skin lesions, which were fairly different from each other. Some of them were cancerous and some of them were not. We had different degrees of accuracy with those different lesions. For example, [with] melanoma, we actually had 100% accuracy because melanomas have a very distinct look.”

Still, even the hardest types of irregularities for the AI to classify hovered around 95 percent accuracy, which demonstrates how promising this technology is.

In order to really strengthen the abilities of the Al when classifying skin lesions, Ackleson’s team used 10,000 photos from a database and manipulated them to make them less visually identifiable.

“In a professional medical setting, you’ve got a dermascope, you can zoom in, [and] there’s lots of clarity and good lighting,” Ackleson said. “[However], in a phone app, that’s not really the case. Lesions start at the single cell level and start to grow from there.”

By changing the lighting and the color of the photos, the AI learned to look for other clues, some that would be challenging for the human eye to pick up on. As the AI is still in early stages, the goal is to give it more images and introduce it to other types of lesions and skin irregularities.

This technology has the potential to save families from losing a loved one and could also greatly benefit hospitals and doctors. There is still room for improvement, but, as of right now, the potential of the instrument is vast and it can only get better.

“Assuming we can get a high degree of accuracy [with all types of lesions], it [will] reduce strain on the healthcare system,” Ackleson said. “If you have someone who detects a lesion on their own at home and it’s not cancerous, like a mole, that person won’t have to go to a dermatologist and have unnecessary surgery on an incorrectly identified growth, or even have it evaluated. That creates more space in the dermatologist’s office or the hospital for people who have actual skin cancer or are in need of immediate surgery.”