Closer to change

The school’s walkout against sexual assault, its leaders, and what comes next

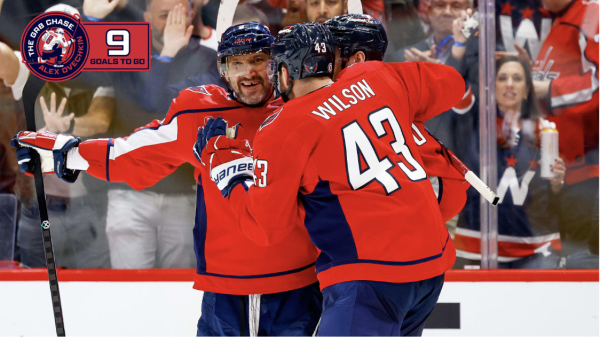

Walkout leaders stand in front of a crowd in protest of sexual assault in Arlington Public Schools. The walkout took place on October 22 this school year.

Amongst all places, school is where most parents expect their children to feel safe. However, this is not always the case due to what many view as the underlying problem of sexual assault and harassment in schools.

On October 22, students at the school walked out of the building during Generals Period and into the neighboring Quincy Park to protest the issue, as planned by senior and lead organizer of the event, Semira Lewis. According to Lewis, the idea for the walkout was prompted by alleged incidents of sexual assault and harassment at Yorktown High School.

“Around the time of homecoming, we started hearing about what had [allegedly] taken place at Yorktown, and how the survivors were not allowed to say much about it, since they didn’t want the reputation of the [perpetrators] to be damaged,” Lewis said. “On the Monday [after], I was sitting in my English class, and just everyone was active on the senior group chat, [we have of roughly 200 people] discussing it…At lunch [I realized] that we needed to do something about this at W-L, and at all Arlington County schools.”

However, the walkout was about sexual assault as a whole in Arlington Public Schools (APS) and what are to many its controversial policies on the matter.

“Sexual assault is an issue overall, [not just triggered by a specific event],” Lewis said. “I went to go and look at the APS policy about it, there was like half a page about student to student sexual misconduct and it basically just said to tell a teacher. The only thing that really was specified was sexual misconduct from a teacher towards a student.”

Senior Grace Gent, who helped Lewis in organizing the walkout, voiced similar concerns based on experience.

“There’s no easy way to report student to student harassment, or at least it hasn’t been communicated with us,” Gent said. “I’ve gone to pretty much every home football game since my freshman year, and I do not have enough fingers and toes to count the number of times I’ve been catcalled at those games, and I have no idea how to report them.”

Gent also pointed out the absence of this discussion in the school system.

“I’ve been going to this school for four years, and the topic has never been discussed in a health class,” Gent said. “We’ve talked about what consent and sexual assault are, but never what to do if you actually are sexually assaulted or harassed…If APS feels they have a strong policy, they should tell students this policy, and incorporate it into the curriculum.”

Senior Savvy Thompson, who joined in efforts to create change within APS after the walkout, has similar feelings.

“In my opinion, [consent] should be taught starting in elementary [school],” Thompson said. “There are ways to subtly introduce this into curriculum, which I think is important because sexual assault and harassment can happen at any age…, not just high school, and in middle school especially. You can’t just start teaching consent in high school and expect behavior that’s already happened to change.”

During the walkout, senior Sara Berhe-Alba made a speech echoing many students’ feelings on the commonality of sexual assault and harassment in the school system, which Gent found particularly powerful.

“She asked everyone to raise their hands if they knew someone who had been harassed during their time at APS, whether by a teacher or another student, and about 75 percent of the hands in the crowd went up,” Gent said. “She then asked people to keep their hands up if they felt like justice had been served in those instances, and about only two hands stayed up. It was really powerful, and at the same time incredibly disheartening.”

Lewis also remarked on the power of the sheer volume of participants in the walkout and its success, despite what some felt was a short period of time.

“The turnout was so big,” Lewis said. “Extremely big. When I left the building [to attend the walkout] at around 10:55 a.m., I started walking and there were so many people behind me; it was crazy. Some people were disappointed in W-L’s [walkout] because it was quite short, but it was harder to have it much longer [without it completely interrupting the school day].”

Planning for the walkout, which occurred at all APS high schools including Arlington Tech and H.B. Woodlawn was also somewhat challenging.

“We suggested that [the other high schools] do something similar at the same time, just at a different location since our schools are so far apart,” Lewis said. “[One challenge that arose was] the day before [the walkout], we were told by administration that students would not be able to come back into the school [after participating] in it….[However, we were able to find] a rule that students were allowed to leave during the school day once per year [to participate in activism], and not be counted with an unexcused absence…so we confirmed people could come back in.”

As for the aftermath of the walkout, Lewis has specific goals.

“We want to strengthen the APS sexual assault policy and make it more specific,” Lewis said. “Assaulters should get actual punishment, and we also would like to hold a convention so that people can learn more about sexual assault in our schools. It would be great as well if we could have it discussed more in health classes, and have a safe space for survivors to talk about their experiences… We also would like to have a town hall with the school board so that we can share the changes that we want to be made, and why.”

To help in this effort to generate change, Lewis, along with others, are in the process of creating various resources to help survivors and spread awareness.

“After the walkout, we made a group chat with a lot of the people involved, and have had Zoom calls to discuss what we want to happen now, after the walkout,” Lewis said. “I’ve [also] created an Instagram page for survivors within APS to tell their stories anonymously [@survivors_in_aps]. We’re including all of APS in this, because the more schools involved, the more safe and anonymous the survivors could feel. Another goal we have is for the page to help spread awareness, and hopefully educate people more on the issue.”

Gent and Lewis also addressed the challenges that will come with ensuring these prospective changes happen.

“The change that needs to be done is very long-form, and it’s realistically never going to stop needing to be done,” Gent said. “Rape culture is intrinsically ingrained in our system, and it’s not only difficult from a systemic perspective to speak up against it, but emotionally as well. Trying to get over that mental hurdle can be really challenging. An environment has to be fostered that is visibly and aggressively supportive of victims and survivors, and that takes a lot of time and effort.”

However, the importance of doing so in this moment, to Gent, outweighs the obstacles.

“[Right now], people don’t really want to punish perpetrators because they’re ‘nice’ or score a lot of points during the football game,” Gent said. “Then, everyone else gets shoved to the side, and it’s appalling. It’s hard, because everyone talks a big game, but what gets overlooked is the question of ‘who’s actually doing anything?’ The ones who [are] are the people who are talking in the group chat about the issue, having those Zoom meetings, brainstorming, and taking those next steps.”

Those helping are mostly seniors at the school, something Thompson and others would like to change.

“I would absolutely encourage underclassmen [to join in the effort],” Thompson said. “This is going to be their movement in the future, because oftentimes, it takes more than a few months or years for things to change… . For anyone who’s nervous about hopping in, know that your voice is valuable, no matter where you are [in school]. You’re going to be the future of this.”

As of December, progress has only begun.

“We want to be able to give this movement the appropriate attention and focus that it deserves,” Thompson said. “January, once college apps are done, I think this will really [begin to happen].”

Once college applications are finalized, the organizers aim to accomplish their goals.

“Hopefully, we’ll be able to have sit down conversations [with the school board], and the Instagram account will be up and running, along with concrete action items that we’ll have,” Thompson said. “I think a lot of this movement is based around conversation, and I believe every good activism is, so when we start having conversations with school board members, school administrators, students and parents, I think that’s where we’re really going to find our strength and hit our stride.”

Thompson hopes people will take away the importance of recognizing and acting on sexual assault and harassment observed in their communities.

“I think the most important thing is for people to call it out when you see it,” Thompson said. “Make sure you’re not tolerating it in your own friend group or in your own life, and that you hold others to that standard.”

To join in the effort, Lewis recommends this:

“I’ve made a Google form for people to share their ideas as to what to do next.” Lewis said. “The more [ideas] the better.”

- For more information on how perpetrators are punished currently in APS, view this link: https://www.crossedsabres.org/news/2022/01/24/aps-handling-sexual-harassment/