Lockdown procedures in APS

How they work, and their role in recent scares

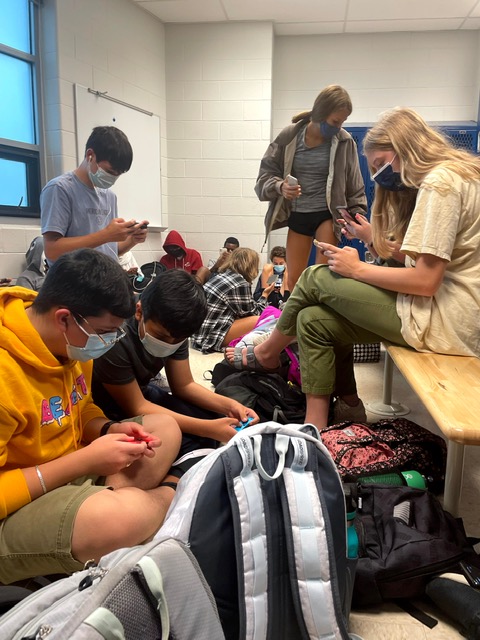

Students hide in the locker room during the October 6 lockdown. They were later released by ACPD.

On October 6, the school was placed under a lockdown just before 8 a.m., due to an anonymous caller falsely claiming there to be an active shooter in the building. Similarly, on February 10, Yorktown was placed under lockdown in the middle of the school day, due to an anonymous caller falsely claiming to be armed with hostages inside one of the school’s bathrooms. These incidents, while separate, have spurred some in the Arlington Public Schools (APS) community to raise questions about lockdown procedures, as well as how these procedures are put into action in times of emergency.

Junior Henry Frickert, who was inside the school during the October 6 lockdown, described the initial announcement of lockdown.

“I went into the cafeteria and I met up with a couple of my friends,” Frickert said. “[Soon], the PA system went off incessantly about lockdown, but it was also kind of glitchy and frazzled. We couldn’t really understand what was going on. We all just kind of sat there. Then they went over the loudspeaker again more clearly saying, ‘We are in a lockdown. This is not a drill,’ and that’s when everything kind of started and they moved us into the gym.”

The gym was eventually deemed unsuitable.

”The gym, I think, was probably where I was most frightened,” Frickert said. “Not super, super frightened, but I was like, ‘Yeah, no, if somebody was actually here and coming…we’re all just kind of sitting in a wide open space.’ …We sat in the bleachers for a little bit and then eventually they moved us into a locker room where we stayed for a few hours.”

While this movement from the gym to the locker room may have appeared unsafe, Frickert stated that he felt otherwise.

“All the movement happened behind locked fire doors,” Frickert said. “They closed all the doors in the hallways to make sure no one could get into the hallways and then they moved us through the hallways to get into a locker room…. [where] I felt very secure.”

During his time in the locker room with what he assumed to be roughly 60 other students, Frickert remained in contact with friends and family.

“I was texting a lot of my friends, calling my family…, everyone was checking in to make sure I was okay,” Frickert said. “A lot of my friends weren’t in the building and were asking what it was like [inside].”

As the lockdown continued, rumors began to develop, reaching students in and outside of the school.

“Some kids started to spread a rumor that there was someone walking around the school in a hood and with a gun, which obviously wasn’t true, but it was a little scary to hear,” Frickert said. ‘I wasn’t too worried about it though, [because] I was like ‘you know, people just spread rumors [in situations like these].’”

Roughly three hours after students and staff at the school had originally moved to the locker room, dispatchers from the Arlington County Police Department (ACPD) knocked on the door.

“The police came into the locker room and we all had to leave the building, showing our hands, keeping our hands in the air, which was a little frightening, because I’ve never been through anything like that,” Frickert said. “They were holding actual machine guns and assault rifles. You don’t see that very often, especially in a school. It’s a little jarring, but it was okay. Everything went smoothly, and we managed to get outside.”

Frickert sympathized with Yorktown students in wake of their recent scare, which he learned about from friends at Yorktown.

“I think at Yorktown it might have even been worse to happen in the middle of the day — most people weren’t even in the building when we had ours,” Frickert said. “Unfortunately, I was, but I know I talked to some of my friends at Yorktown and they were very scared because they were in their classrooms, which is obviously terrifying.”

In the aftermath of the Washington-Liberty lockdown, Frickert reflected on the effectiveness of the lockdown procedures.

“There weren’t any real hiccups in the plans, but some people were a little confused,” Frickert said. “I noticed people asking like, ‘Okay, what do we do now?’ especially when we were in the gym or in the cafeteria. And they eventually came with a plan to move us around. So it was planned, but no, I don’t think everybody knew what was going to happen…. There wasn’t really anything I would change.”

Frickert especially valued the support of teachers throughout the lockdown.

“The teachers were definitely trying to make sure we were comfortable, which I appreciated,” Frickert said. “They got us through it and they didn’t lose their cool; they were always calm and collected. I think [that] helped some other people also stay calm and collected.”

Similar to Frickert’s description, teachers outside of the school during the lockdown helped to evacuate arriving students. This included Mrs. Christina Steury, who arrived shortly after the lockdown had been announced.

“Initially, I got back in my car, because we were told to get back in our cars and stay in place, so we all did that, but we were still communicating with each other,” Mrs. Steury said. “Then we started seeing kids walking through the parking lot, and we were like, we can’t just sit in our cars and not help them…. We all started getting out of our car[s], and then we were told that we needed to usher them across the street… and some teachers stayed behind to help kids get on buses.”

Teachers’ leadership aided in what many viewed as the day going as smoothly as possible, given the circumstances. However, in the wake of the scare, some have wondered if lockdown drills should be practiced at varying times of the school day for safety reasons; this would include the beginning of school, during lunch, passing periods, and after school. Currently, they are not practiced during these times.

“The logistics of…[having lockdown drills before, after school, during lunches, and during passing periods] sounds like a nightmare, but I do think it’s important to know [what to do] if you’re in the middle of the hallway,” Mrs. Steury said.

Mrs. Steury had some unease toward a different aspect of lockdown.

“[Another concern would be] that students who have had historically, you know, kind of uneasy relationships with the police definitely had a different reaction to this, and being forced to put their hands up,” Mrs. Steury said. “A typical white person like me, who’s never had a bad interaction with a police officer, might not feel quite as threatened when they come towards me.”

Mrs. Steury also spoke in relation to the Arlington County Police Department [ACPD] in general.

“We hope this isn’t the case, and I think there’s a pretty good reputation in [the ACPD],” Mrs. Steury said. “I had a student who ended up in the building, who had [previously had] some uneasy run-ins with the police, and he said he got very defensive…. I think it’s important to make sure that there’s an understanding that everyone comes from a different place.”

Deputy Chief Wayne Vincent, head of ACPD’s Community Engagement Division, stated that ACPD recognizes this importance.

“When it comes to when we respond to a lockdown or critical incident or active incident in the school, race for us does not play a part,” Deputy Chief Vincent said. “Our job there is to neutralize the threat and there is a way that we would determine what a threat is, often the most obvious [way] being someone who is actively trying to hurt people in the school. On top of that, our officers also trained very often every year, when it comes to things like cultural diversity, cultural awareness, [and] various sets of soft skills as well as implicit bias. Not to mention, our policy is very explicit, as far as the way we treat people not based on their race, gender, sex, sexual orientation, so forth and so on.”

Since the elimination of School Resource Officers (SROs) from APS schools due to student requests and concerns over racial inequity, police are no longer involved with lockdown drills. A School Board vote in June 2021 made this a reality.

“Virginia State Code mandates that each public school have at least four lockdown drills per year,” Deputy Chief Vincent said. “When the SROs were in the schools, we helped facilitate that with APS. You don’t need a school resource officer or a police officer to do a lockdown drill, but because we were in the schools and because our officers knew the schools and staff, we helped facilitate those lockdown drills with them. Since being removed from the schools, we were no longer asked to help facilitate those lockdown drills.”

However, ACPD still remains a part of implementing lockdown procedures.

“When and if we are notified of a lockdown at a school, we can send out a party one call, meaning that a significant amount of police resources will respond to a school to neutralize any threats and to ensure that the campus, the students and staff are safe,” Deputy Chief Vincent said.

Open discussion between APS and ACPD is also fostered.

“A couple of years ago, we sat down with APS and public safety to talk about what our procedure [was] going to be if indeed a fire alarm was pulled,” Deputy Chief Vincent said. “If you think about it, even during a lockdown situation where all the kids are following the procedures inside of a locked classroom, again, one wall away from the door if you hear a fire alarm, you’re going to think obviously ‘fire’ when it could be a tactic used to get everybody outside the room into the hallway and into danger.”

Another procedure that APS follows during lockdown is the use of red and green placards. This procedure is similar to the procedures that students will not be released from lockdown by announcement or from classrooms upon the sound of a fire drill.

“If you’re in lockdown position procedures, and you’ve got the door locked to any classrooms, you would use a red placard if you have a medical emergency in your room,” Deputy Chief Vincent said. “That way, while officers are going into schools, they at least can identify ‘this room has a medical emergency.’ In the very same case, if you use a green placard, that means everything is okay. We want to get to those rooms [with red placards] first to get that person medical care.”

For threats outside of the school, lockdown procedures are not enacted. Instead, a procedure known as “secure the school” takes place.

“The difference between secure the school and lockdown is simply [that] the threat is inside the school versus outside the school,” Deputy Chief Vincent said. “In the last two cases at W-L and Yorktown when those respective administrators called for a lockdown, they felt that more than likely that there was a threat inside the schools. That’s why, as opposed to a secure the school situation where you can still go up and down the hallways, in a lockdown, [for students, it’s] ‘let’s get out of the hallways and let’s get into our classrooms. Let’s lock the doors and let’s go through our normal procedures.’”

Recent scares at the school and Yorktown have been identified as hoaxes by ACPD within hours, which some in the APS community have voiced concerns over in relation to the time it takes for this identification to occur.

“For us to call something fake or a hoax, that’s an investigation obviously,” Deputy Chief Vincent said. “You’re hearing about it [being a hoax] afterwards, but sometimes it takes some time for us to determine if something is real, a real hoax or not, so that’s not something we take very lightly. A lot of factors are going to come into play before we would make that call that this is potentially a hoax and even if we do call something a hoax or, or you know, a joke or prank, we would still proceed with the utmost caution to ensure the campus is safe. Always.”

Deputy Chief Vincent made a final remark.

“I know that the latest incident can be viewed as traumatic, but you can rest assured that the police department is here to ensure a safe community and if any parent or teacher has any concerns or questions, they can always feel free to contact me or the Community Engagement Division,” Deputy Chief Vincent said. “We’ll be more than happy to answer any questions that we can answer.”

To conclude his reflection on the scare at the school, Frickert said this:

“The next day [of school after the threat] was a little weird because we got a full day off [the day of], obviously,” Frickert said. “But then after that, everything kind of went back to normal. It wasn’t that traumatizing of an experience, not something I think about a lot. If anything, it makes me feel better, because now I know that in a real situation, there is a plan. They know what they’re doing, which I like.”

*Disclaimer: APS Safety, Security, Risk & Emergency Management did not respond for comment. Additionally, some questions Deputy Chief Vincent declined to answer in order to not give away police tactics. Both scares at the school and Yorktown remain active investigations.

What did you think about this story? Do you have any suggestions for improvements or other articles that you would like to see? Please use the contact form to communicate with us! (Keep all information school-appropriate)

https://docs.google.com/forms/d/e/1FAIpQLSeRYRWwLLzvs2rqwHSGdr-DQRvxhUSx9UcaXypXxnvVuCqwyA/viewform