On the first day of school in 1947, Constance Carter entered Washington Liberty (then Washington-Lee) and was immediately turned away, all due to her race. 100 years later, Washington-Liberty’s student population is majority-minority.

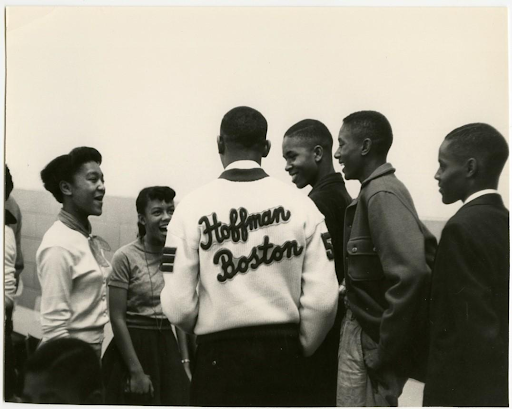

Washington-Liberty first opened its doors in 1925. The school opened as a white school, and white students were segregated for years to come. The local black school, Hoffman-Boston, had seen an overhaul of black students following a 1946 ruling from Washington D.C., stD.C.g that they would no longer provide black students from Arlington County Countyion into their schools free of charge.

“The burden upon the county authorities became more onerous when in recent years the schools in the District of Columbia imposed a tuition fee upon students from Arlington County and discontinued the practice of admitting black high school students from the county free of charge.”

Initially, most black students went into the city for school, as Hoffman-Boston did not adequately provide most classes required to graduate. While the population of black students in Arlington bordered on 5%, Hoffman-Boston was still overrun with students and not adequate for housing all the learners.

Carter, requesting Typewriting, Physical education, and Spanish – walked into the halls with her mother as well as NAACP representative Eleanor Taylor. Washington-Liberty principal Claude Richmond refused Carter’s request, citing the Commonwealth’s requirement that all public education be segregated. Carter and Taylor filed suit with the help of NAACP peers, being represented in court by Spottswood W. Robinson III and Martin A. Martin. In such a lawsuit, attention was drawn to the lack of facilities, classes, and community extracurriculars at Hoffman-Boston.

The suit pointed out the various activities W-L provided, in contrast to the all-black school,

“The white pupils at Washington-Lee enjoy various extracurricular activities, such as glee clubs, choruses, cadet corps, publication staff, Hl-Y organizations, debating club, and various athletic teams, and are eligible for nomination to the National Honorary Scholastic Society and for] the receipt of the Bausch and Lomb Honorary Science award. None of these activities and awards are available to the colored pupils at Hoffman-Boston”

The case didn’t just point out the unfair conditions of both schools, the case made it very clear that this prejudice was race-based.

“The above recital of existing conditions at the two schools is not intended to cover the whole field of physical plant and instruction, but rather to demonstrate by illustration that discrimination in the treatment accorded the students of the two races undoubtedly prevail.”

Another source explained that the path to desegregation was not exactly easy.

Washington Liberty High School has had a complex history over the past 100 years it’s been open, Carter was one of the first to oppose any attempt to change these oppressive norms. History is ingrained within our walls, unavoidable, and impossible to ignore. These changes manifested in the subsequent name change, letting go of the ‘Lee’ at the end.

The questions arise, should our school community continuously take accountability for our racist past? Should we teach about the injustices within our walls that started with Carter? Or should we exercise the privilege of ignorance? Should we leave this racist past behind and start a new chapter? Should we strive to forget and create a new legacy for the school? How does one balance the complex history?

The importance of remembering Carter and the legacy she left behind is paramount. The teen was faced with hardships following the case, “To apply to a white school became a trigger for hate phone calls, hate mail, and cross burnings. Local churches, black and white, as well as civic groups, continued the struggle, nonetheless, to desegregate Arlington’s public schools.”.

Modern-day Arlington country remains overwhelmingly progressive, so it comes as a surprise to learn about the racism that used to take place.

“This seems to be the theme of Arlington Public Schools throughout the entire integration process – public support of public education. The process was by no means easy or painless, but quite the opposite. Arlington County continued with a gradual process of desegregation. With a combination of school closings, school construction, redistricting and eventually busing, the schools began to achieve some racial balance.”

This doesn’t just apply to the county, it’s in these very walls in which Carter was refused. Understanding our school’s history as we celebrate 100 years since its opening complements our responsibility of leaving its legacy.