The county’s push for more equitable practices in schools has resulted in the implementation of a new test retake policy. It stems from a book called “Grading for Equity: What It Is, Why It Matters, and How It Can Transform Schools and Classrooms” by Joe Feldman. The goal of the retake policy is for students to focus more on understanding the content in their classes rather than solely focusing on their grades. However, teachers are finding that it often has the opposite effect and creates more work for teachers and students.

“I don’t think it’s actually beneficial for students,” said Mr. Jim Zarro, a math teacher at the school. “[I] tried retakes a long time ago, and I found that students … either did worse or if they did better, it was only a couple of points better. It ended up being a lot of extra work on both teachers and students with little to no benefit.”

He explained that the extra work can further impair a student’s ability to succeed in the class.

“While I’m teaching unit 2, [students are] still trying to learn unit 1,” said Mr. Zarro. “Then they fall behind on unit 2 … so they don’t do as well on that test, and then they’re behind on that and … it [ends] up just being more work and not showing more understanding.”

Teachers found that too many students are retaking exams that already have passing grades.

“I do think that [retakes are] more, for students, about getting the better grade,” said chemistry teacher Ms. Erin Smith.

Mr. Zarro expressed similar findings about his students.

“One thing I … don’t like is that a lot of students who have A’s and B’s are trying to retake it just to get a higher grade,” said Mr. Zarro. “I had a student that got a 96 who wanted to do a retake.”

Ms. Mackenzie Fusco, a history and social anthropology teacher at the school, explained that she does not think the retakes necessarily have the desired effect.

“Most of the students retaking have an A or a B in the class and … usually [got] a B or a C on the test,” said Ms. Fusco. “It is rare that students who got D’s or E’s on the test, or have that grade in the class, are retaking the assessment.”

Teachers have expressed concern over this trend.

“Even the students who have an 80, you’re showing mastery with [that],” said Ms. Smith. “So, why do you feel like you need to take it again? I just wish that more students that either failed or got below … a 70 would … retake because then the chances of them doing the remediation and getting a higher grade are … pretty high … But they won’t, and I’m not going to force them. It’s up to them to want to do better.”

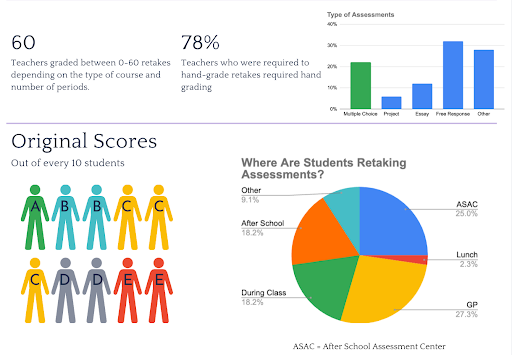

Ms. Crystal Liller is in charge of the after-school assessment center (ASAC), where many retakes occur, and polled teachers about the exams. She found that about 35% of the students retaking exams this year had an original grade of either an A or a B.

A couple of potential solutions offered by teachers included implementing restrictions on retakes, such as a maximum grade on the initial exam to be eligible or a maximum number of retakes allowed per class. Such changes could cut down on the extra work for teachers and allow them to devote more time to the students who genuinely need help like the policy initially intended.

Only about a quarter of the re-administered exams were self-grading versions such as Scantrons or Canvas quizzes. The remaining three-quarters of the tests must be hand-graded by teachers, adding to their already heavy workloads.

“In my IB classes, [the] tests are all mostly short answer and it takes time to grade them, and grade them effectively and then provide feedback,” said Ms. Smith.”[It] puts on a whole lot more work because you’ve already graded one, and now you’re grading a second. [It] has put a substantial amount of work … on teachers to have to do this for every summative assessment that we have.”

She added that the extra workload was noted by the county and brought up at school board meetings. The remediation process required before retakes also adds work to teachers’ plates. Humanities teachers face an additional challenge in figuring out how to remediate non-traditional assessments such as Socratic seminars and projects.

“In order to really do better on the retake, the remediation has to have a certain amount of detail and rigor,” said Ms. Fusco. “So to make the remediation, to look over the remediation and talk with students about what they were not successful on the first time can definitely be time consuming.”

Students hold differing views on whether or not the remediation and retakes are worth the effort.

“For me personally, I actually don’t have that many students that take advantage of [the policy], especially in my general classes. [In] my IB classes, I have more,” said Ms. Smith. “I don’t have that many students because in order for them to retake it … remediation is required, and I find that they would rather take their lower grade then do the remediation.”

Ms. Fusco added that it can be daunting and intimidating to completely redo an assessment you failed the first time.

“I think that if you’re a student who really struggled on an assessment, to basically put yourself through it again can be kind of hard to talk yourself into,” said Ms. Fusco. “And if you feel like okay, I got a D or an E, I really don’t understand this, I think that maybe some students feel like how much better am I really going to get at it in two weeks?”

Ms. Liller also collected information about what teachers were doing for remediation, and responses ranged from seeing the teacher during GP to completing test corrections to reading the textbook for two hours.

Additionally, teachers have noticed discrepancies between who is taking the exams again, with many finding that IB/AP students are typically more likely to retake. Possible explanations include the natural difficulty of the classes and the somewhat perfectionist mindset of some students in those classes.

I think that for a lot of students … if you’re in a heavy AP or IB class load, it is often because you’ve been successful [earlier] in school,” said Ms. Fusco, “and so you have a desire to continue that success. Often we think of being successful as getting a good grade.”

Partially as a result of this tendency, upperclassmen also appear to be retaking more assessments than underclassmen are. The retakes have varying impacts on students’ grades though.

Mr. Zarro shared that for one test in his IB SL math class, he had about 20 students retake the exam. Of those students, one person scored two points higher than they did originally but most people did a couple points worse, with some even doing significantly worse.

“I’ve had students during the test ask when the retake is,” said Mr. Zarro. “As a student, if you have that in your head that if I don’t do well, I do take the retake, I find that a lot of students don’t put their full effort forward because they’re like, well, it doesn’t really matter.”

Ms. Fusco found that most students score better on retakes in her class, but it is typically a very minimal increase in their grades.

“A lot of my retakes are students who get a B on the first attempt and a B+ on the second attempt or a B+ on the first attempt and an A on the second attempt,” said Ms. Fusco. “There’s not often a jump where I got a C on the first test and an A on the second one.”

Part of this is because the remediation process is not always enough to help the student with the more significant issue or concept they are struggling with.

“If there’s an aspect of writing that someone is struggling with, the remediation can help you make a small improvement on that,” said Ms. Fusco, “but we’re not … necessarily going to jump from really struggling with a writing concept to excelling at it.”

Another barrier to scoring higher on a retake is when students need to put their full effort into the remediation assigned.

“Those that really want to improve their grade go home, study, do the remediation, come back, and improve [their grade] even if it is by 5%,” said Ms. Smith. “Then there are always those students who rush through the remediation, turn in whatever I require them to turn in, and just kind of hope for the best and so … they typically don’t get a higher grade.”

Ms. Fusco explained that in her IB anthropology class, about 50% of the class retook the first exam, but since then she has only had a couple of students per exam that want to retake. Part of this, she shared, is because the first test is often the hardest as students are still getting used to that teacher’s specific testing style.

“I also think that as the year goes on, students just get really busy,” said Ms. Fusco. “Everybody’s in clubs, they’re playing sports, the amount of work they have in their classes is ramping up, and so taking the time to do the remediation and the retake might become harder because [they] have so many other things going on.”

Ms. Smith also commented on students’ packed days.

Most [students], I would say, take [the retake] during GP even though that’s a shorter period of time this year just because they have so many other commitments after school,” said Ms. Smith. “I’ve had only, I think, one student use the after-school test center.”

Despite this, retakes have significantly impacted the number of students attending the ASAC, which recently opened on Saturdays to accommodate the increased demand.

“The testing center … started about 5 or 6 years ago. I created it for people who were absent [because] if you miss a test, it’s really hard to make up a test during GP or lunch,” said Ms. Liller. “[This] kind of became more of a problem during COVID because you know, a lot of people were out for longer periods of time, they had a lot to make up, so it got a little more popular … Now with the retakes, it’s just exploding.”

During the 2022-23 school year, the ASAC was used 438 times. As of December 11 of this school year, the ASAC has been used 796 times. The busiest day this year hit 84 students in one afternoon. While it used to be just one or two proctors in a classroom, now that number is four or five because of the greater number of students that need to be helped.

“Now, it’s not uncommon for days where they need to [use] three classrooms,” said Mr. Zarro. “I know it’s stressful for the students too because they’re coming here at 3:10 ready to take the test, but there were days when kids didn’t get signed in until 4 o’clock because everyone has to sign in, get the right test, make sure their stuff is put away … It’s just adding stress to a lot of people and providing minimal benefit.”

Ms. Liller found that students were more likely to use the ASAC on Thursdays than they were to use it on Tuesdays.

These changes are the product of APS’s recent focus on more equitable grading practices to ensure the grading system is leaving no one behind.

“The last couple of years APS has been focused on what’s often called grading for equity,” said Ms. Fusco, “[and] trying to make more equitable grading practices so that more students can have an opportunity to succeed.”

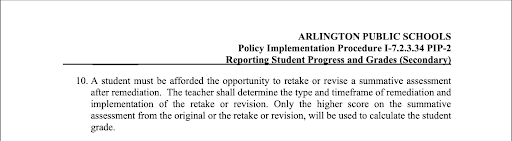

In the last couple of years, APS had had committees of teachers from all of the schools that met a few times during the school year to discuss various grading policies, such as the retakes and late work and how to make them more equitable.

“Coming out of the pandemic, we saw huge achievement gaps,” said Dr. Baskin, the Dean of Students. “The grading policy is one way to impact that, to make sure that everyone has an opportunity to be successful … It’s part of a larger effort to make sure that schools are really responsive to the needs of every student.”

Dr. Baskin and Ms. Fusco were both representatives for the school on the county-wide grading committee last year. The committee sent their proposed changes to APS leadership, who revised the proposals before sending them to the school board. The board then approved the changes at the end of the school year. This year, another committee has been put together to figure out ways to make the current policy more effective.

“They have another group meeting this year to talk about … now we’re in year one of this, how are the changes actually going now that they’re being implemented in the schools,” said Ms. Fusco. “I think when you make a big change like that it’s hard to anticipate what all of the impacts are going to be.”

Last year, the policy was a 50% floor on tests such that any student who demonstrated reasonable effort earned at least a 50 as their grade on said test.

All of these things right are supposed to be done in a way that makes it more equitable to all the students, and I think that they’re really great on paper, but I think the execution maybe isn’t great,” said Ms. Smith. “I want to see [retakes] continued [as] I like this better than the 50% floor because it actually puts a little bit of ownership on students rather than none.”

Overall, teachers shared that they supported the goals of the retake policy but that it needed some changes to make it more effective.

“As a blanket policy … if you talk about economics like the cost-benefit analysis, I don’t think the benefit is there. I think the cost in terms of extra work for students, extra work for teachers, extra work in the after school testing center just doesn’t provide the benefit that other things could provide,” Mr. Zarro said. “Instead I’m grading retakes of students who got an 84.”